Published Work

It Helped Catch Serial Killers. Can It Stop Elephant and Wildlife Poachers, Too?

Aquariums Hatch Unusual Plan to Save Endangered Zebra Shark

By Catherine M. Allchin

Science Magazine

A leopard can’t change its spots, and a zebra can’t change its stripes. But the zebra shark has long delighted ocean divers and aquarium visitors with its ability to transform the white bands it is born with into spots as it grows. Now, the endangered shark is grabbing attention for another reason: It’s at the center of an unprecedented effort to rebuild a wild shark population using eggs from aquariums.

“It is very important to us to protect and preserve this unique and charismatic species,” says Charlie Heatubun, a botanist at the University of Papua, Manokwari, and head of Indonesia’s West Papua Research and Development Agency, which is participating in the project.

The distinctive zebra shark (Stegostoma tigrinum, also known as the Indo-Pacific leopard shark) was a popular attraction for snorkelers and divers in Southeast Asia a few decades ago. Considered harmless to humans, the sharks are slow moving and spend most of their time in shallow reef habitats. In recent years, the shark fin trade has decimated S. tigrinum populations. In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) elevated the shark to endangered on its Red List, and it is now likely locally extinct in several areas in Indonesia.

At the same time, zebra sharks are thriving in aquariums around the world. In fact, the animals do so well in captivity that aquariums keep males and females separated to prevent unintentional breeding and production of unwanted eggs. That ready supply of eggs, however, has provided conservationists with an opportunity to repopulate the species in the wild, the Association of Zoos & Aquariums (AZA) announced recently.

Food Gives us Meaningful Connections

The Pie's the Limit

No Run-of-the-Mill Flour

Grains of a Bigger Truth

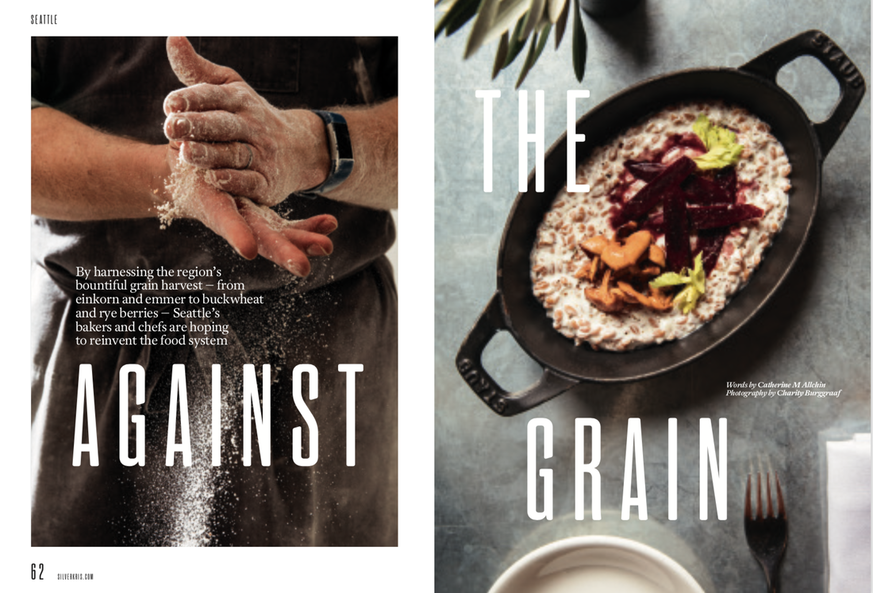

Against the Grain

A Bounty of Simplicity

By Catherine M. Allchin

The Seattle Times

EARLY EVERY MORNING, when the farm is quiet, Haidee Hart starts the fire in the wood stove. The barn kitchen glows with light and warmth, even though it’s dark outside. She makes breakfast for guests, and soon the farm begins to buzz with activity. Hart talks with farmers about what the garden offers that day and then plans lunch and dinner.

Hart is the chef at Stowel Lake Farm, an organic farm and retreat center on Salt Spring Island, B.C. She and her husband, Josh, have raised their four children on the farm, living and working alongside two other families for many years.

It is a special place where young and old live and work together to care for the land and each other.

This vision — of free-range children and sustainable farming in an intentional, intergenerational community — came from Lisa Lloyd, a B.C. native who bought the 115-acre property 40 years ago. After decades of hard work by many, the family-owned farm, retreat center and farmstand are thriving.

As chef on the farm, Hart sees her mission as sharing the beauty of vegetables with guests. “We hope to inspire people to learn the story behind their food and to bring a connection with real food into their lives,” she says.

From the barn kitchen, Hart can see the overwintering celeriac root and parsley in the 4-acre garden. In her cooking, she focuses on the beauty and simplicity of what the garden gives. “When baby carrots first come in, I’ll make a carrot-top pesto, and guests can experience that incredible moment.”

5 Places to Visit in Ketchum, Idaho

By Catherine M. Allchin

The New York Times

Nestled in the Rocky Mountains of south-central Idaho lies Ketchum, an outdoors-obsessed city and home to America’s first destination ski resort, Sun Valley. At 9,150 feet, Bald Mountain, called Baldy, presides over Ketchum with 12 lifts, 105 trails, a sophisticated snow-making operation and impeccably groomed runs. While new hotels (Limelight Hotel on the south end, Hotel Ketchum on the north) bookend Main Street, the half-mile stretch still exudes plenty of the old-time charm from Ketchum’s mining and sheep ranching heyday with cabin-style shops and historic brick buildings. Professional big-mountain skier and native Alexis “Lexi” du Pont describes Ketchum as “classy Western.” She says the area offers a great deal of history and a European influence from Sun Valley resort, which opened in the 1930s, “but at the same time it’s Wild West Idaho.” Here are five of her favorite places.

The New York Times

Nestled in the Rocky Mountains of south-central Idaho lies Ketchum, an outdoors-obsessed city and home to America’s first destination ski resort, Sun Valley. At 9,150 feet, Bald Mountain, called Baldy, presides over Ketchum with 12 lifts, 105 trails, a sophisticated snow-making operation and impeccably groomed runs. While new hotels (Limelight Hotel on the south end, Hotel Ketchum on the north) bookend Main Street, the half-mile stretch still exudes plenty of the old-time charm from Ketchum’s mining and sheep ranching heyday with cabin-style shops and historic brick buildings. Professional big-mountain skier and native Alexis “Lexi” du Pont describes Ketchum as “classy Western.” She says the area offers a great deal of history and a European influence from Sun Valley resort, which opened in the 1930s, “but at the same time it’s Wild West Idaho.” Here are five of her favorite places.

'In a Good Place'

By Catherine M. Allchin

The Seattle Times

“WOULD YOU LIKE coffee? Water? Are you hungry?” Chef John Sundstrom, wearing a characteristic blue apron, opened the door of his Capitol Hill restaurant, Lark.

A warm welcome is typical at Lark, which Sundstrom and his partners Kelly Ronan and J.M. Enos (also his wife) own and operate together. On the restaurant’s 15th anniversary, the chef reflected on his culinary journey and the evolution of Northwest cuisine.

Think back to 2003. Seattle hadn’t embraced the small-plates concept yet. We were comfortable with the traditional categories of appetizers and entrees. Menus didn’t list the specific farms that vegetables came from. Pan-Asian was exciting.

Today, thoughtfully sourced, farm-fresh, shareable food defines Northwest cuisine. And Sundstrom was one of the chefs responsible for that transformation.

When Sundstrom was at Dahlia Lounge and Earth & Ocean in the W Hotel, he developed a network of farmers and foragers. “I’d go to farmers markets and look for a new farmer or a cheese maker, looking to supply great food to the restaurant,” he says.

The Seattle Times

“WOULD YOU LIKE coffee? Water? Are you hungry?” Chef John Sundstrom, wearing a characteristic blue apron, opened the door of his Capitol Hill restaurant, Lark.

A warm welcome is typical at Lark, which Sundstrom and his partners Kelly Ronan and J.M. Enos (also his wife) own and operate together. On the restaurant’s 15th anniversary, the chef reflected on his culinary journey and the evolution of Northwest cuisine.

Think back to 2003. Seattle hadn’t embraced the small-plates concept yet. We were comfortable with the traditional categories of appetizers and entrees. Menus didn’t list the specific farms that vegetables came from. Pan-Asian was exciting.

Today, thoughtfully sourced, farm-fresh, shareable food defines Northwest cuisine. And Sundstrom was one of the chefs responsible for that transformation.

When Sundstrom was at Dahlia Lounge and Earth & Ocean in the W Hotel, he developed a network of farmers and foragers. “I’d go to farmers markets and look for a new farmer or a cheese maker, looking to supply great food to the restaurant,” he says.